- Home

- Geoffrey C. Bunn

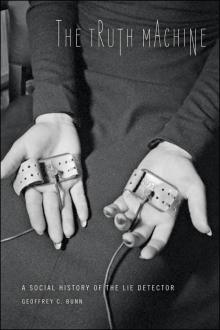

The Truth Machine

The Truth Machine Read online

The Truth Machine

JOHNS HOPKINS STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF TECHNOLOGY

Merritt Roe Smith, Series Editor

The Truth Machine

A Social History of the Lie Detector

Geoffrey C. Bunn

© 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bunn, G. C. (Geoffrey C.)

The truth machine : a social history of the lie detector / Geoffrey C. Bunn.

p. cm. — (Johns Hopkins studies in the history of technology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-0530-8 (hdbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-0651-0 (electronic)

ISBN-10: 1-4214-0530-x (hdbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4214-0651-9 (electronic)

1. Lie detectors and detection—History. 2. Lie detectors and detection—

United States—History. I. Title.

HV8078.B86 2012

363.25 4—dc23 2011044971

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information,

please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected].

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials,

including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste,

whenever possible.

What therefore is truth? A mobile army of metaphors, metonymies, anthropomorphisms: in short a sum of human relations which become poetically and rhetorically intensified, metamorphosed, adorned, and after long usage seem to a nation fixed, canonic and binding; truths are illusions of which one has forgotten they are illusions, worn-out metaphors which have become powerless to affect the senses; coins which have their obverse effaced and now are no longer of account as coins but merely as metal.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense” (1873)

It is so easy to do wrong! Everything the Devil makes runs easily. It is only God’s machinery which has friction. The lie is spontaneous;—the truth requires thought. Yet the offhand production is born with the seeds of decay in it, and its other name is “Death.” Its history is always cyclical, and returns upon itself; for the path of a lie is so tortuous that, sooner or later, it is bound to intersect its own course. Then comes discovery, humiliation, pain—retribution. The hyperbola of deception has never yet been plotted.

—Milton L. Severy, The Mystery of June 13th (1905)

CONTENTS

Introduction

Plotting the Hyperbola of Deception 1

Chapter 1

“A thieves’ quarter, a devil’s den”: The Birth of Criminal Man

Chapter 2

“A vast plain under a flaming sky”: The Emergence of Criminology

Chapter 3

“Supposing that Truth is a woman—what then?”:

The Enigma of Female Criminality

Chapter 4

“Fearful errors lurk in our nuptial couches”:

The Critique of Criminal Anthropology

Chapter 5

“To Classify and Analyze Emotional Persons”:

The Mistake of the Machines

Chapter 6

“Some of the darndest lies you ever heard”:

Who Invented the Lie Detector?

Chapter 7

“A trick of burlesque employed … against dishonesty”:

The Quest for Euphoric Security

Chapter 8

“A bally hoo side show at the fair”:

The Spectacular Power of Expertise

Conclusion

The Hazards of the Will to Truth

Acknowledgments

Notes

Essay on Sources

Index

The Truth Machine

INTRODUCTION

Plotting the Hyperbola of Deception

An increased liberalism in the definition of “fact” can have grave

repercussions, while the idea that truth is concealed and even

perverted by the processes that are meant to establish it makes

excellent sense.

—Paul Feyerabend, Against Method (1975)

On January 30, 1995, not long after O.J. Simpson had released I Want to Tell You, the book he hoped would clear his name, the tabloid television show Hard Copy revealed that they had subjected the double murder suspect to a lie detector test. The former football star had recorded himself on tape, reading aloud various passages from his book: “I want to state unequivocally that I did not commit these horrible crimes.”1 Hard Copy hired lie detector expert Ernie Rizzo to use a “Psychological Stress Evaluator” to subject Simpson’s voice to stress analysis. According to the show’s “Hollywood Reporter,” Diane Dimond, the test could separate “fact from fiction.” Used by the police, the military, and big business, the instrument had been shown to be “95 percent accurate.” As a result of Rizzo’s analysis, he concluded that Simpson was “one hundred percent deceitful … one hundred percent lying.”2 One week after Hard Copy’s deception test, supermarket tabloid newspaper the Globe subjected the same tape recording of Simpson’s voice to “Verimetrics,” a hightech lie detector favored by police investigators.3 But this time Jack Harwood, a “Veteran investigator,” proclaimed Simpson “absolutely truthful,” noting that the “lie test shows O.J. didn’t do it!”

One type of lie detector, identical statements from a single suspect, and two equally emphatic yet contradictory verdicts. When Simpson said, “I would take a bullet for Nicole,” Harwood claimed, “the former football hero was being completely honest,” while according to Rizzo he was “absolutely lying.” How can two experts both claim scientific validity for their respective instruments, analyze the same material, and reach completely different conclusions?

Early histories of the lie detector celebrated the many famous and infamous cases in which it had been used during the twentieth century.4 More recent studies have either challenged the instrument’s scientific status, or questioned its legitimacy on grounds that this practice constitutes an assault on civil liberties.5 David Lykken was one of the first psychologists to dispute claims about the machine, arguing, “the lie detector has no more place in the courts or in business than a psychic or tarot cards.”6 According to Lykken, by 1980 more than one million lie detector tests were performed annually in the United States.7

The classic polygraph examination involves simultaneously measuring a suspect’s blood pressure, breathing rate, and electrical skin conductance as a series of questions that require yes or no answers are asked. But the person can also be subjected to more covert scrutiny: “behavior symptoms” are observed before and after the test is performed; cameras behind two-way mirrors may record gestures and nuances of expression. Talkativeness and enthusiasm may be noted, to be incorporated into the examiner’s final assessment of truth or deception. It seems that no lie detector examination takes place under “objective” scientific conditions divorced from the wider social context. And symbols lend insight into the values that underscore the lie detector test. What better emblem of masculine professional power than the briefcase, that mandatory accessory of every polygrapher? From the black briefcase comes the chart, at once a graphic calculus of guilt an

d a sacred scroll inscribed with the truth. Consider also the chair, a seat for the sovereign subject with whom no eye contact must be made, but also a constraining device, reminiscent of the electric chair.

The demarcation between the supposed rationality of the male polygrapher and the supposed apparent emotionality of a female subject is a salient feature of lie detector discourse. The instrument was designed to reveal the supposed invisible pathologies of the female body, an approach with a long precedent in criminology, a history that this book examines. For the science of “pupillometrics”—the attempt to detect dishonesty by recording changes in pupil size—the gaze of the subject becomes the important characteristic of the deception test. In a recapitulation of criminal anthropology’s fruitless search for visible stigmata of criminality, almost every body part has been subjected to testing: the hand, arm, skin, lungs, heart, muscles, voice, stomach, and brain have all been examined at some point in the history of this technology. Sometimes it has not just been the human body that has attracted pioneers. In the late 1960s, Cleve Backster achieved international notoriety for attaching his polygraph to a philodendron plant, claiming it could detect “apprehension, fear, pleasure, and relief.”8 A former Central Intelligence Agency interrogator and director of the Leonarde Keeler Polygraph Institute of Chicago, it was Backster who introduced the “Backster Zone Comparison Polygraph,” which became the standard polygraph model used at the U.S. Army’s Polygraph School. By 1969 it seems he had single-handedly created the urban legend that plants had emotions: “We have found this same phenomenon in the amoeba, the paramecium, and other single-cell organisms, in fact, in every kind of cell we have tested: fresh fruits and vegetables, mold cultures, yeasts, scrapings from the roof of the mouth of a human, blood samples, even spermatozoa.”9

The traditional polygraph measures skin conductance, breathing rate, and blood pressure. The subject also undergoes intense visual scrutiny.

Cleve Backster, a polygraph expert for the CIA, attempts to detect deception in a plant. Photo by Henry Groskinsky, Life.com images.

Between the 1935 Lindbergh “crime of the century” and the 1995 O.J. Simpson “trial of the century,” the notion of the lie detector became deeply embedded in the North American psyche. Despite constant criticism, satirical attacks, government prohibition, Papal condemnation, and a widespread suspicion that it “can be beaten,” the use of the lie detector persists. High-profile cases in which the participants took polygraph tests include cases involving Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas, the spy Aldrich Ames, and the Oklahoma City and Atlanta Olympics bombings. Isuzu trucks, Pepsi Cola, and Snapple juice are some of the products that were advertised with the help of the “truth machine.” It appeared in countless movies and television shows. In one Star Trek episode, Captain Kirk made Scotty take a lie detector test to prove he was not a serial murderer of women. An episode of the 1990s hit TV cop show Homicide featured “the electro-magnetic neutron test” which, unknown to the suspect, issued photocopies of a palm print upon which the words “True” or “False” had been printed beforehand. Many such depictions, of course, portray lie detection as a rational and technical science by contrasting it with “pseudoscience.” But use of the machine has constantly transgressed the boundary that supposedly demarcates factual science from sheer fantasy.

The use of the lie detector to manage contradiction is a key theme of this book, one that previous histories have not highlighted. The principle ambition here is to investigate how the lie detector came to be constructed as a technology of truth.10 Why do these machines continue to feature in the dreams of those responsible for maintaining law and order? Recent scholarship has detailed the biographies and motivations of the major actors in the historical drama.11 My aim is to push the story back in time into the obscure origins of criminology itself. What interests me is why and how the lie detector was finally “invented” in the United States, even though all the important technological innovations had been developed by European criminologists prior to the start of the twentieth century. My argument is that the machine came about as the result of a sustained dialogue between science—in this case criminology—and the wider culture. Literary, newspaper, and movie depictions did not misinterpret, distort, or corrupt the concept of the lie detector; in fact they played a vital role in creating it.

CHAPTER 1

“A thieves’ quarter, a devil’s den”

The Birth of Criminal Man

There is a thieves’ quarter, a devil’s den, for these city Arabs.

There is their Alsatia; in the midst of foul air and filthy lairs they

associate and propagate a criminal population. They degenerate

into a set of demi-civilized savages, who in hordes prey upon

society … a race as fierce as those who followed Attila … These

communities of crime, we know, have no respect for the laws of

marriage—are regardless of the rules of consanguinity; and, only

connecting themselves with those of their own nature and habits,

they must beget a depraved and criminal class hereditarily

disposed to crime. Their moral disease comes ab ovo.

—J. Bruce Thomson (1870)

For much of the last two millennia in the West, the Christian tradition considered the miscreant’s deeds to be manifestations of universal sin. Human weaknesses such as depravity, temptation, lust, and avarice were regularly invoked to account for conduct that compromised the moral order. Criminality was explained by appealing to supernatural forces such as the actions of mischievous demons or the vagaries of fate. People in early modern England believed that God exposed and punished the crime of murder either through direct intervention or by acting through temporal agents.1 The supreme power of divine providence guaranteed that crimes of blood would be punished, despite the difficulties associated with detection and proof.

In 1591, a Kent coroner ordered the murderers of four children to call out their names, whereupon the victims’ pale bodies, “white like unto soaked flesh laid in water, sodainly received their former coulour of bloude, and had such a lively countenance flushing in theyre faces, as if they had beene living creatures lying aslepe, which in deed blushed on the murtherers when they wanted grace to blush and bee ashamed of theyre owne wickednesse.”2 In the 1650s, Lady Purbeck and a maidservant were both instructed to lay their hands on the corpse of an infant discovered in a privy. The maidservant immediately confessed to the murder when the body started bleeding.3 In 1725, London magistrates ordered that a human head found on the shore of the Thames at Westminster be placed on a pole in a nearby churchyard, directing church officials to arrest anyone “who might discover signs of guilt on the sight of it.”4 Locals recognized the head as that of John Hayes, whose wife, the magistrates quickly discovered, had recently taken two lovers. Convicted of the murder, Catherine Hayes was subsequently burned alive. As these examples demonstrate, in the early modern period, corpse touching, cruentation rituals,5 and violent public executions appeared to materialize divine intelligence; they produced confessions and acted as powerful deterrents against crime.

Such procedures were products of mental frameworks and ways of life very different from those of our own era.6 Modern ideas about criminality originated in the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Cesare Beccaria in Italy, Jeremy Bentham and John Howard in Britain, Benjamin Rush in America, and Paul Johann Anselm von Feurerbach in Bavaria pursued rational inquiries into the causes of crime and prison reform, pioneering a secular, modernist criminological discourse.7 Rush’s The Influence of Physical Causes upon the Moral Faculty (1786) was one of the first scientific attempts to conceptualize crime and insanity in terms other than sin.8 Bentham described his innovative model prison, “Panopticon” of 1785, as “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.” The ambition of what later became known as the “classical school” was that “government by rule” would replace “unregulated di

scretion,” in the words of one magistrate reformer.9 Such beliefs were based on a rationalist conception of the calculating subject, a model of the individual whose “psychological” motivations were irrelevant to the administration of justice. Under this framework, research into the biological or environmental causes of crime would only undermine the liberal conviction that individuals were autonomous agents in full control of their own actions.10

The general thrust of penal policy during the nineteenth century was humanist. The number of hangings declined in England from the 1830s, and by the 1860s all the traditional Georgian penalties had been abandoned, including the pillory and whipping post, the convict ship, and the public execution.11 Public violence was increasingly thought to pander to the lowest human instincts and militate against improving the conduct of the population. Punitive spectacles were gradually replaced by measured disciplinary techniques. The prison was rejuvenated as a space for moral discipline, “a training ground for, and a social representation of, the overcoming of immediate impulses and passions and the reconstruction of character.”12 Punishment strategies that had once broken the body transmuted into to those that promised to repair the mind. These reforms brought the hitherto indistinct image of the criminal into sharp focus.

At the start of the nineteenth century, the criminal had been little more than “a pale phantom, used to adjust the penalty determined by the judge for the crime.”13 By its end he had eclipsed the crime and had become the focus of criminological discourse. A diverse array of intellectual, scientific, practical, social, and political developments combined to create an empirical discipline devoted to systematically analyzing the causes of criminality.14 New theories of human nature conceptualized the mind as a natural entity, particularly in the wake of evolutionary theory.15 The reconceptualization of human agency in the language of naturalism made it possible to think about criminality less in terms of moral failures of the will and more in terms of the mind’s constitutional and environmental influences. Scientific explanation began to shift “from acts to contexts, from the conscious human actor to the surrounding circumstances.”16 Geniuses, criminals, and the insane populated the new disciplines—the three types of exceptional people that had inaugurated the anthropological study of human beings in the late eighteenth century.17 The “insane criminal genius”—that diabolical combination of all three foundational categories of the human sciences—inhabited the pages of learned journals and was thought to stalk the streets of the metropolis.

The Truth Machine

The Truth Machine